Mental Wellbeing, Religion and the Love You Give

Rapid Report

The Global Mind Project

MARCH 25, 2024

From Our Founder & Chief Scientist

And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love. 1 Corinthians 13:13

Love is one of the most mysterious aspects of human life – intangible and yet implicitly understood by us all. It is the force that drives us to act in ways that are self-less, to look beyond greed and envy, to help one another and to find forgiveness and reconciliation. In every religion from Christianity to Islam to Buddhism, love for others holds a prominent place.

Research has found that love, spirituality and religion are all associated with greater mental wellbeing, but what is their relationship? In this report based on a sample of 239,692 internet-enabled people across 65 countries that cover all major religions, we begin to untangle this relationship. We ask how one’s spirituality (or lack thereof) relates to the love you feel for others, how active religious practice drives spirituality and love, and whether love and spirituality have distinguishing impact on mental wellbeing. In some respects the answers are surprising.

We find that spirituality is associated with a greater extent of love and care for the wellbeing of others, while atheists are five times more likely to love and care for no-one. We find that irrespective of religion, active religious practice is associated with greater spirituality, and in turn, greater love for others. Most profoundly, however, the increases in mental wellbeing associated with greater love and care for others are almost the same regardless of whether atheist, agnostic or spiritual, actively practicing a religion, or associated with none. Said another way, religious practice and spirituality appear to enhance your wellbeing by expanding the love you feel for others. And while one can come to love and care for others by various paths, active religious practice can more reliably lead you there, but is by no means a guarantee.

This study is part of the Global Mind Project which collects mental wellbeing data in 14 languages across 65+ countries. The Global Mind Project uses a comprehensive assessment of mental wellbeing called the MHQ which covers 47 elements of mental feeling and function along with detailed demographics, lifestyle, and life experience factors. For this study, four additional questions were included that probed 1) the level of spirituality (on a scale from atheist belief to strong connection to a higher power), 2) the extent of love and care for the wellbeing for others, 3) religious identity and 4) active practice of one’s religion.

As always, this data is openly available to the research community. We offer this as an initial view and invite researchers to probe this important topic in greater depth.

Tara Thiagarajan, PhD.

Founder and Chief Scientist

Executive Summary

Research Question

This report examines the extent to which people feel love for others (i.e. family, friends, community), how this relates to their mental wellbeing, and how this is influenced by their level of spirituality and active religious practice. The findings are based on data from 239,692 internet-enabled respondents across 65 countries, obtained between January 2023 and February 2024 as part of the Global Mind Project. Data were collected using an assessment called the Mental Health Quotient, or MHQ, which assesses 47 aspects of mental feeling and function that are aggregated into a overall mental wellbeing score. The assessment also collects data on demographic, lifestyle and life experience factors including people’s extent of love and care for the wellbeing for others, their spirituality (defined here as a connection to a higher power) and whether they identify with, or actively practice, a religion.

Key findings

- Those who are spiritual love and care for the wellbeing of a wider circle of people, while those who are atheist are five times more likely to love no-one.

- The increase in mental wellbeing gained through spirituality arises through the increase in one’s feelings of love and care for others, and spirituality without love and care for others does not have mental wellbeing benefits.

- Active religious practice is associated with a higher likelihood of spirituality and love for others, regardless of religious affiliation.

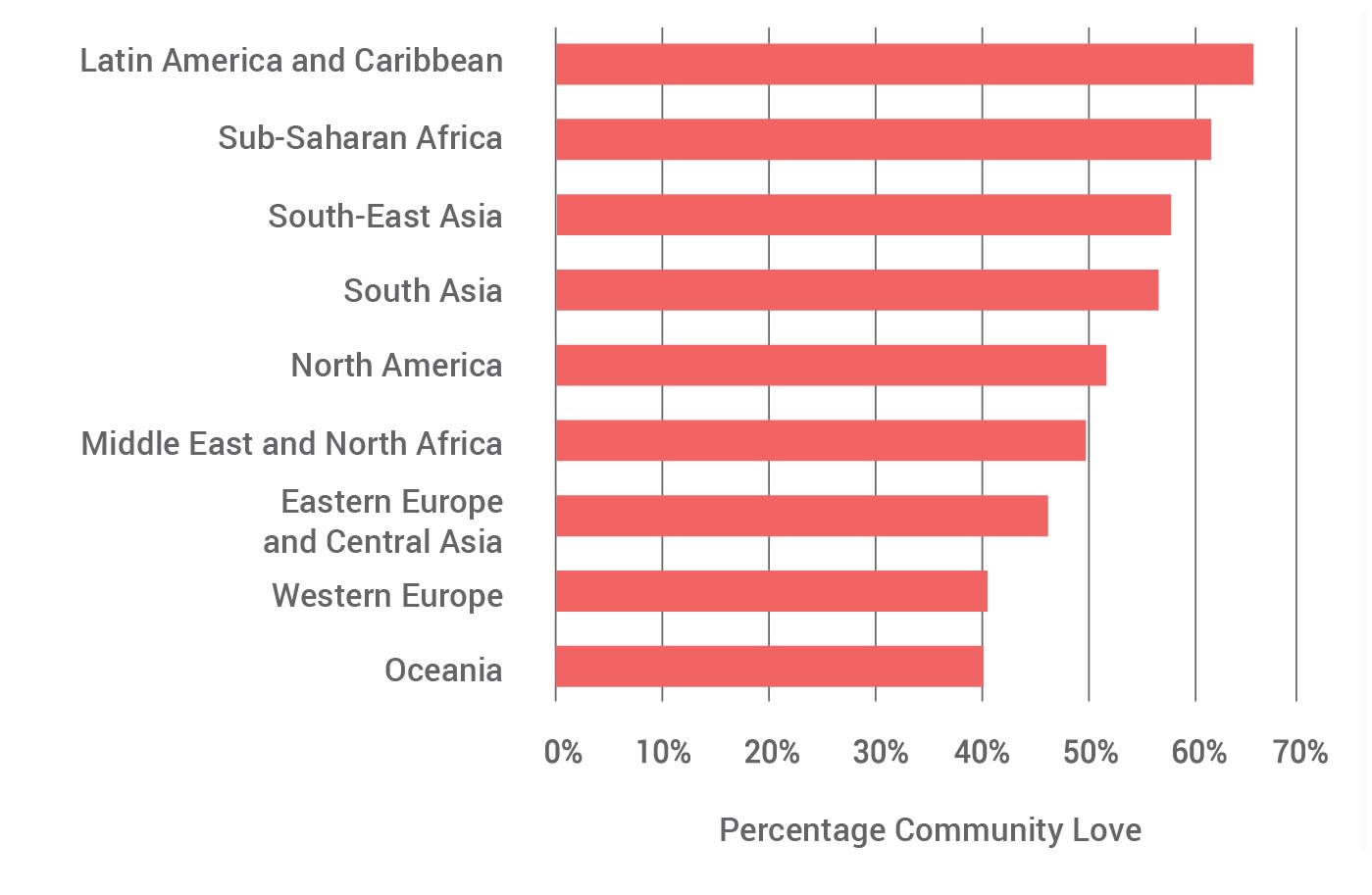

- More religious regions of the world have greater love for others led by Latin America, South-East Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Europe and Oceania have the least love for others with United Kingdom and Germany having the lowest among all countries from which data was collected.

Conclusion

Spirituality and active religious practice appear to enhance your mental wellbeing by expanding the love you feel for others. And while one can come to love and care for the wellbeing of others by various paths, active religious practice is a relatively reliable one, but is by no means a guarantee.

Introduction

As human beings, we have an innate capacity to love and care for the wellbeing of others. Although we often consider this in the context of caregiving roles as a parent or family member, this capacity also extends beyond our kin, to caring about and wanting to promote the wellbeing of other people in our wider social circle including friends, acquaintances, people in our community, and even extending to people we don’t personally know.

This capacity to love and care for others, not only benefits those in our family and community, but has also been shown to benefit our own psychological wellbeing and physical health, improving self-esteem and reducing feelings of depression1. In addition, it promotes social connection, enhances belonging, and strengthens the social relationships and bonds that are so critical for our wellbeing.

Although there are multiple societal scaffolds that promote care for others in the community, and in turn our collective wellbeing, one such scaffold is spirituality and religion. Many religions around the world have loving others (sometimes called compassionate love) as a central tenet to their scriptures, and religious activities often strengthen social connection across the community. This connection is reinforced by studies showing that religiosity and spirituality are positively associated with compassionate love for close others (i.e. friends, family) as well as for humanity (i.e. strangers)2.

In addition, research studies from around the globe have increasingly highlighted the positive relationship between religious beliefs and spirituality and mental health and wellbeing3. In particular, having religious beliefs or spirituality is associated with fewer symptoms of depression, a lower incidence of suicide, lower severity of alcohol or substance use, and improved coping with adverse life events4–8. Furthermore, research looking at how religious beliefs and spirituality impact the brain have revealed changes in brain structure and function that are proposed to contribute to these protective effects 9,10.

However, across much of the Western world, there has been a steady decline in the active practice of religion. For example, recent reports from Gallup and Pew Research Foundation have shown that in the United States, there has been a steady decline in the importance of God and an increase in the number of people identifying as non-religious, while in Europe, the number of actively practicing Christians has steadily declined11,12. However, this contrasts with other regions (e.g. Africa, Latin America) and religions (e.g. Islam) where religious salience remains high13,14.

Concurrently, in some populations around the world, evidence suggests that the love and care we feel for others in our community is on the decline. For example, in the United States studies suggest a generational increase in narcissism, resulting in lower empathy, less concern for others, and less civic engagement15. Other studies have suggested a global increase in individualistic practices and values over collective ones16.

This rapid report probes the relationship between these various factors: love and care for others, mental wellbeing, spirituality, and religious practice, and how they relate to global trends in wellbeing. It describes how one’s spirituality (defined here as a sense of connection to the divine) relates to one’s feelings of love and care for the wellbeing of others; how active religious practice (e.g. attending services, reading scriptures) relates to these feelings of love and care; whether love for others and spirituality have distinguishing impacts on people’s mental wellbeing.

About the Global Mind Project

The Global Mind Project is the largest and most comprehensive study of mental wellbeing in the world. Spanning 65+ countries in 14 languages, it currently collects 1000-2000 new data responses each day and, since 2020, has collected responses from over 1.4 million internet-enabled people around the globe.

The project uses an assessment called the MHQ which collects data across 47 aspects of mental wellbeing, together with information on demographics, lifestyle, and life experience, including love for others, spirituality, and religious practice (see methods for more information on the assessment). It therefore provides a unique opportunity to study the interaction between these factors in a large, globally diverse population. The data from this ongoing study is openly available to academic and nonprofit research organizations.

Key Findings

1. Spirituality and love for others

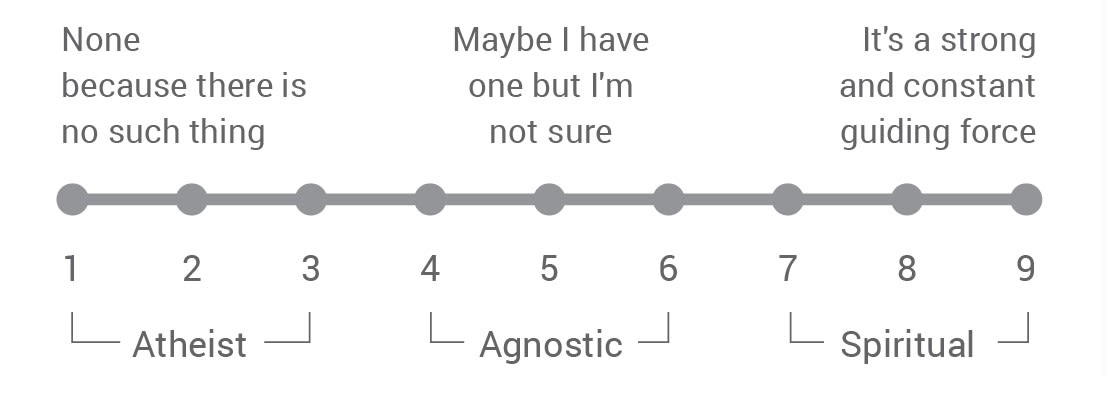

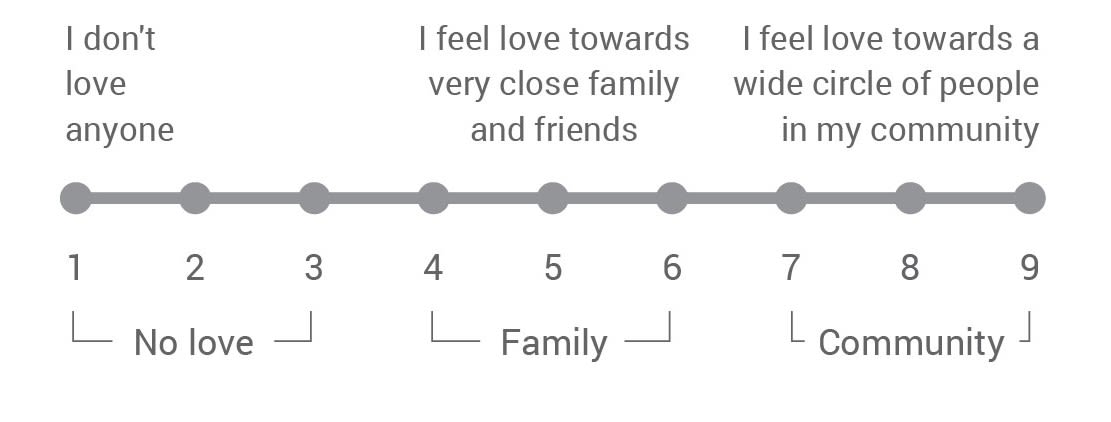

72% of those with high levels of spirituality (Spiritual group; see figure below for an explanation of how these groups were defined) love and care for a wide community of people beyond their close family and friends, while only 4% indicate love for no-one or fewer people than their close friends and family (No love group). This was in stark contrast to those with no/low levels of spirituality (Atheist group) where only 35% indicated love and care for the wellbeing for a wide circle of people beyond their close friends and family and 23% indicated love for no-one. Those in the Agnostic group (who were not sure about a connection to the divine) were in between these two groups (but closer to Atheists), with 43% indicating love for a wide community and 8% indicating love for no-one.

Thus, spiritual people are twice as likely as atheists to love and care for a wide community of people, while atheists are five times as likely to love no-one. The correlation between spirituality ratings and love ratings is 0.7 overall. However, it is also important to note that atheism does not preclude love and care for the wellbeing of a wide community of people and spirituality does not guarantee it.

“Spiritual people are twice as likely as Atheists to love and care for a wide community of people, while Atheists are five times as likely to love no-one”

Figure 1: Extent of love for others by Spirituality

How do you describe your sense or feeling of connection to a higher power or divine?

Assess the extent of your feelings of love (a desire for wellbeing) for others

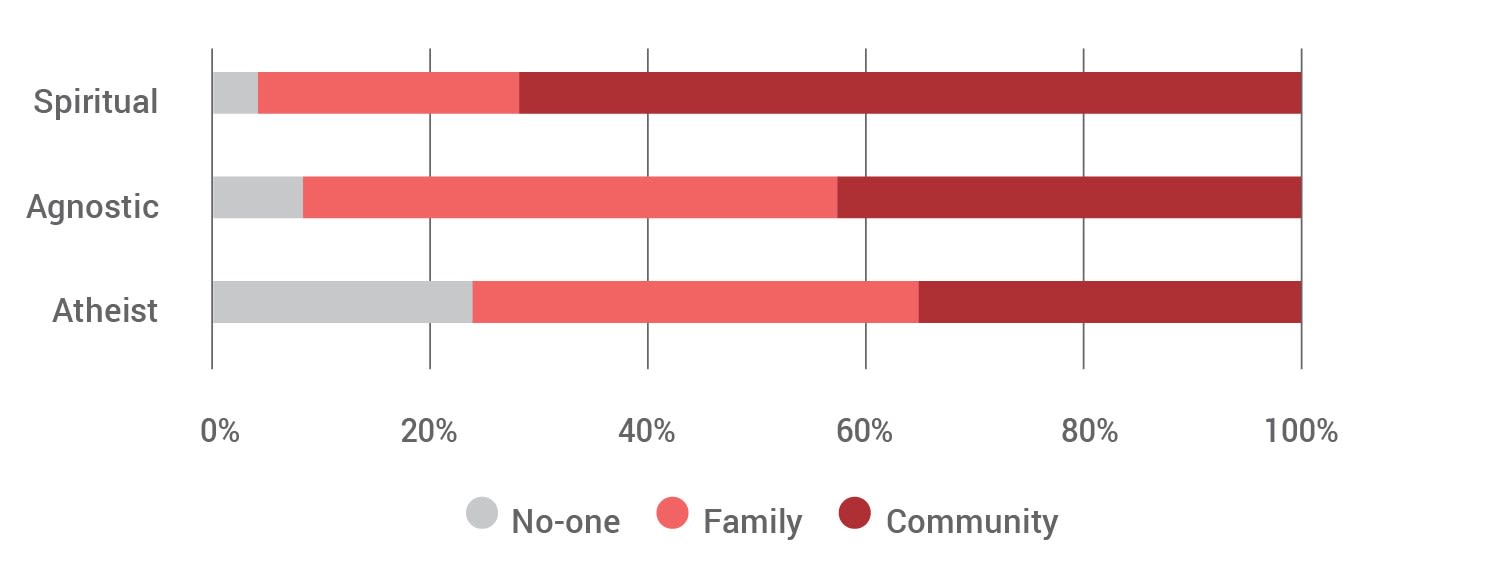

2. Spirituality, love and mental wellbeing

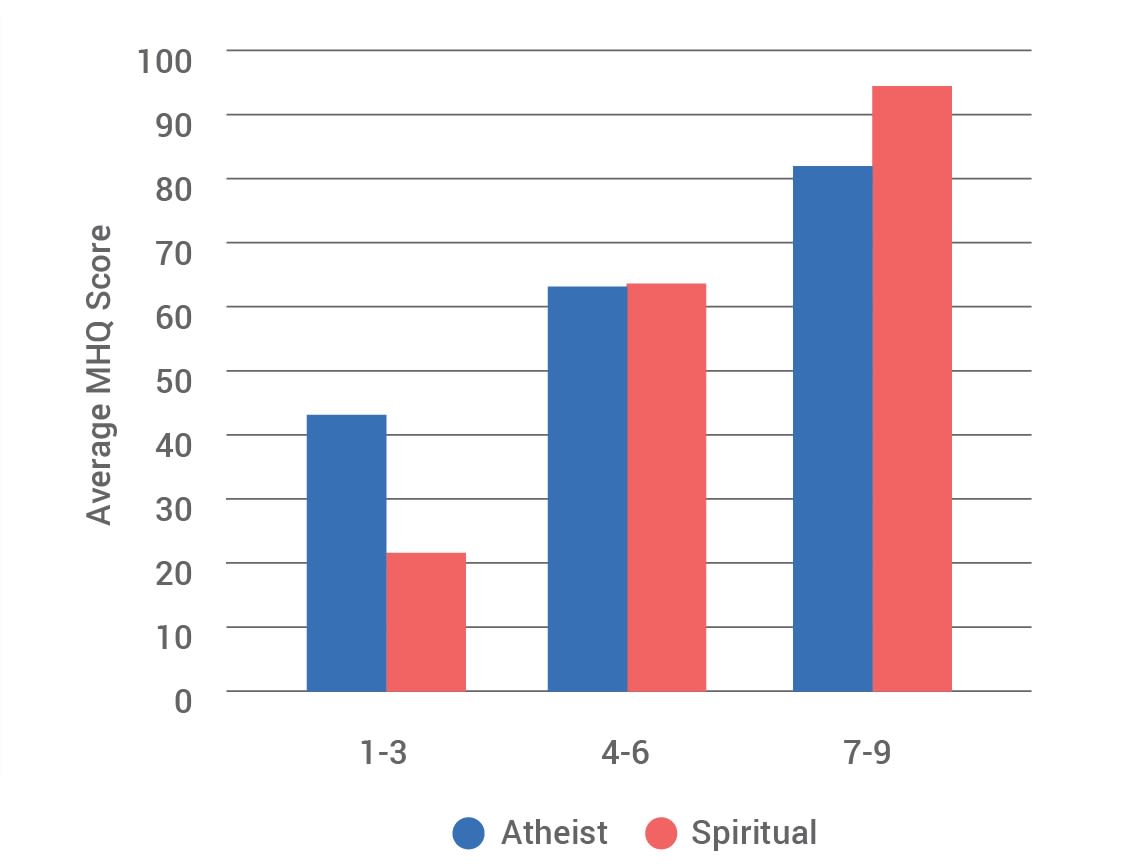

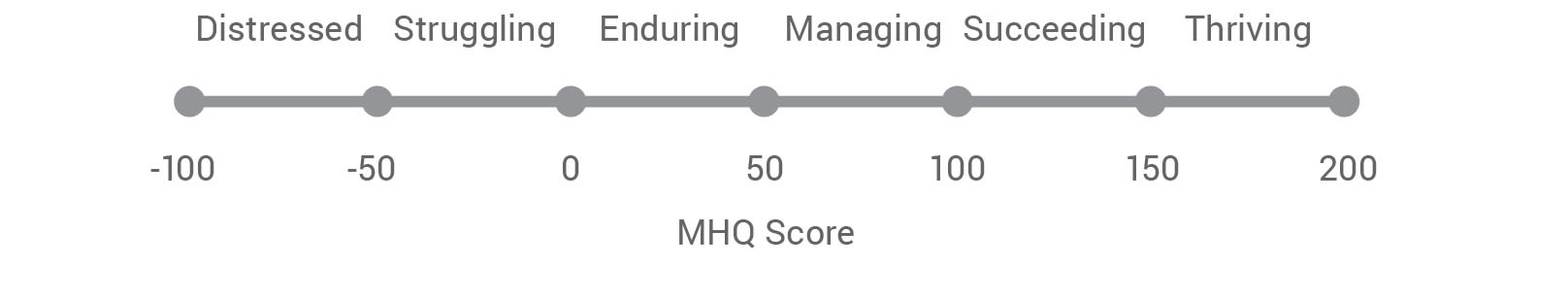

Here we show the relationship between the MHQ, a metric of mental wellbeing, and love for others for the Atheist and Spiritual groups. The MHQ is an aggregate score than integrates ratings on 47 aspects of emotional, social, cognitive and physical feelings and functions to position individuals on a spectrum from distressed to thriving and is described in detail here.

MHQ scores were highest for those in the Spiritual group, while those in the Atheist and Agnostic groups, had similarly lower MHQ scores (left panel). However, for both the Atheist and Spiritual groups, MHQ scores increased as the love score increased such that there was only a small difference between Atheist and Spiritual group for those with the highest extent of love and care for others (right panel). On the other hand, atheists with little or no love for others fared better than those who were spiritual but had little or no love for others. We also note that the dimension of mental wellbeing that increased most significantly with greater love was Adaptability & Resilience. Cognition increased the least, though still significantly.

This suggests that the increases in mental wellbeing gained through spirituality arise through increased love and care for others, and that spirituality without love and care for others does not have mental wellbeing benefits. However, it also shows that while spirituality is a reliable path to feelings of love and care for others, it is not the only path.

"Increases in mental wellbeing gained through spirituality arise through increased feelings of love and care for others."

Figure 2: Mental wellbeing by spirituality and extent of love and care for others

MHQ Scale

3. Active religious practice and love

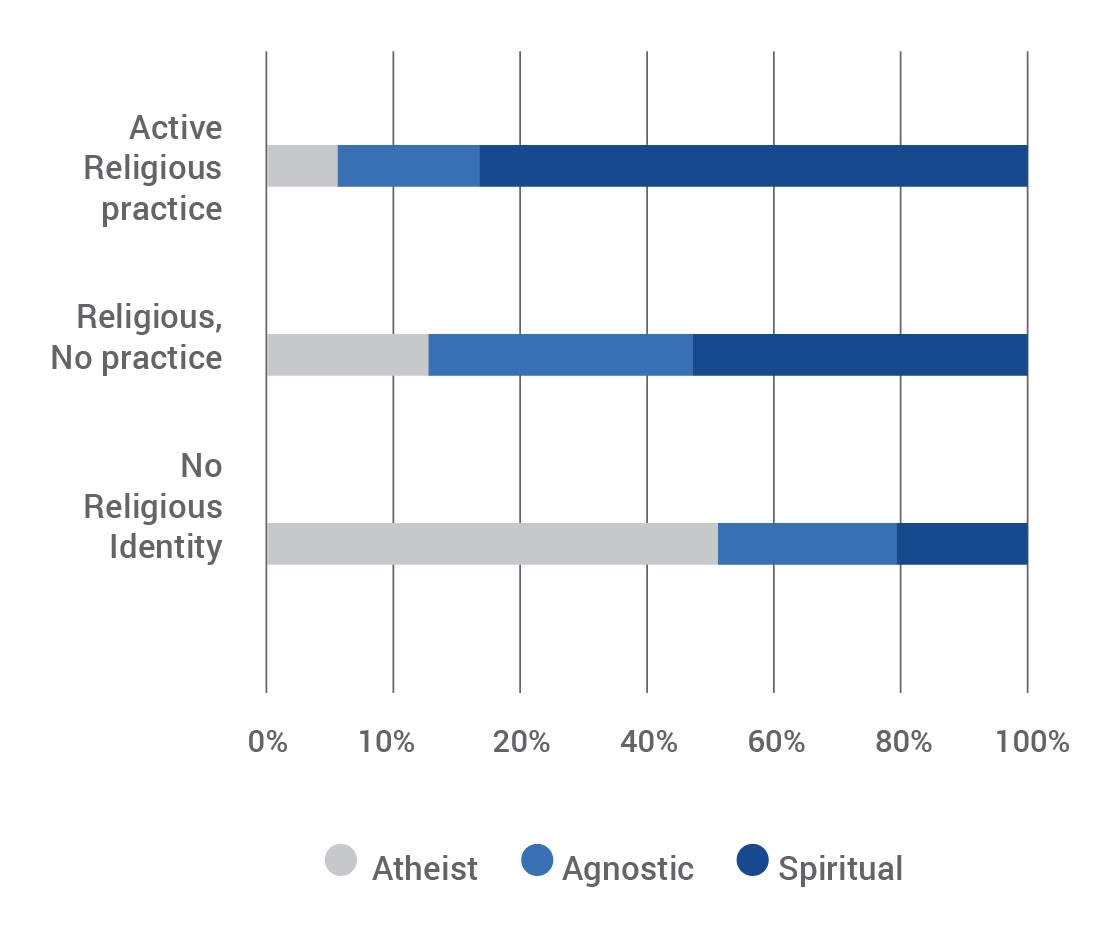

Spirituality, or a sense of connection with the divine, is often associated with religion and religious practice. Here we look at whether religious affiliation and active practice (defined here as attending services, practicing rituals or prayers, reading scriptures) increases feelings of spirituality and love and care for others.

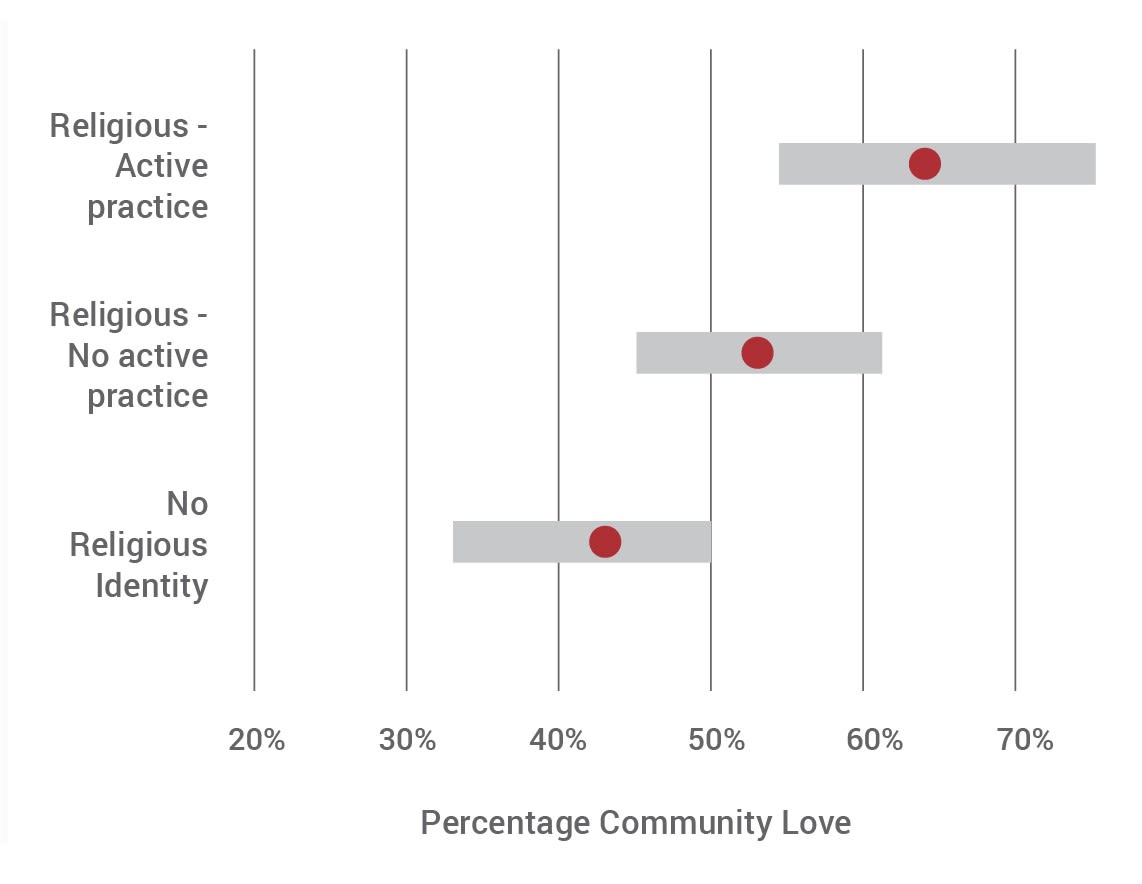

Among those who identify with a religion and actively practice that religion, 72% are also spiritual compared to only 44% of those who identify with a religion but do not actively practice it (left panel below). In contrast, among those who do not identify with any religion, only 17% were spiritual. So also 64% of those who actively practice their religion love and care for a wide circle beyond their close family and friends, compared to 53% of those how do not actively practice their religion, and 42% of those who did not identify with any religion (right panel).

However, while these are global averages, there was a wide range across all 65 countries that we looked at, which spanned North America, Europe, Latin America, Middle East, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, South East Asia, Central Asia and Oceania. For those who actively practiced their religion, the range across these regions was from 54% to 76% (shown in the grey bar, right panel), while the range was 36% to 49% for those who do not identify with any religion.

Altogether this suggests that active religious practice offers a relatively reliable path to spirituality and in turn love for others. However, it is also clear that active religious practice does not guarantee spirituality and love for others, and that this may depend on the nature of religious practice and other circumstances and cultural factors that surround it.

"Active religious practice offers a relatively reliable path to spirituality and in turn love for others, but does not guarantee it."

Figure 3: Spirituality and love for others by religious identity and practice.

4. Love in the world

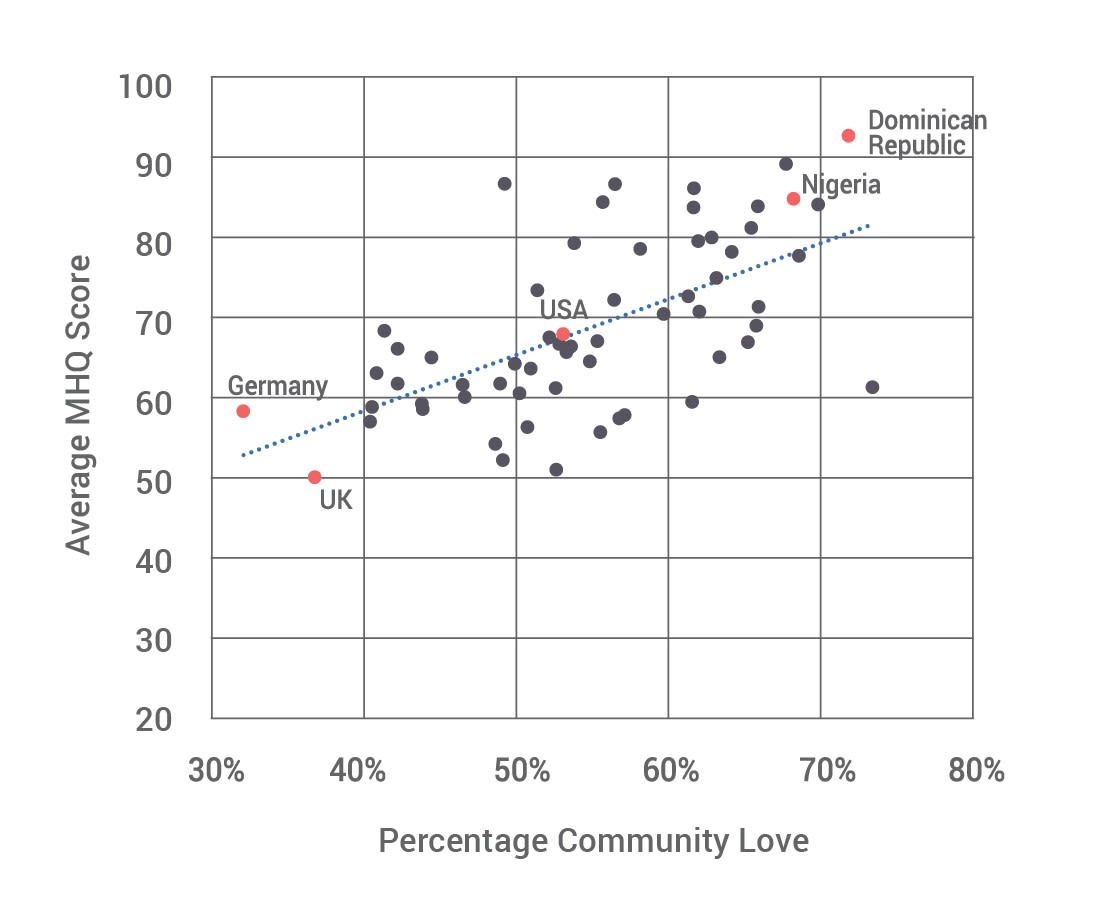

The data from the Global Mind Project reflects a diverse range of cultures and geographies. Here we look at how people’s love and care for the wellbeing of others varies around the world. The graph below shows the regional values for the proportion of the population who report they feel love and care for the wellbeing of a wide community of people beyond their family (left panel), and the relationship between this percentage and mental wellbeing or MHQ scores (right panel). Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa had the most love and care for people beyond their close friends and families (66% and 62% on average respectively) while Europe and Oceania had the least (45% and 43% respectively). At a country level, mental wellbeing scores had a correlation of 0.6 with the percentage of population with a wider extent of love for others (right panel).

Within these regions, the countries with the lowest percentage of love and care for a wider community of people were the United Kingdom (UK) at 37% and Germany at 32%. Correspondingly, in the UK only 46% of respondents still identify with a religion and only 15% actively practice that religion, while in Germany 47% still identify with a religion and only 12% actively practice that religion. We contrast this with Nigeria where 98% identify with a religion, 89% actively practice that religion and 68% love and care for a wider community. The United States falls in the middle with 65% identifying with a religion, 35% actively practicing that religion and 53% with love and care for a wider community. Values for individual countries are shown in the associated data tables. We remind the reader that we refer only to the Internet-enabled populations.

"The mental wellbeing of countries is correlated with the percentage of their population that love and care for a wider circle of people."

Figure 4: Regions and countries with greater love for others have better mental wellbeing

Insights and Interpretations

There have been numerous studies that relate love for others, spirituality, and religion to increased happiness and deeper various mental health benefits1-8. Our findings provide insight into the relationship between religion, spirituality and love, as follows:

Spiritualty is associated with a greater love and care for others

First, we show that those who are spiritual, defined here as having a strong connection to a higher power, feel love and care for the wellbeing of a larger community of people beyond immediate family and close friends. Conversely those who are atheist, defined as those who don’t believe there is a higher power, are five times more likely to feel love for no-one or fewer people than are in their family. Thus, spirituality appears to increase active love and care for fellow human beings. One interpretation could be that God or the divine acts or exerts His will through love for others. However, it is also possible that the beliefs and practices that drive spirituality engender a mind state that is more loving and caring of others.

Mental wellbeing benefits of spirituality are dependent on the love you feel for others

As expected, those who were spiritual had greater mental wellbeing than those who were atheist or agnostic (defined as being unsure about any connection to the divine). However, what was surprising was that there was little difference in the mental wellbeing of spiritual and atheist groups who both love and care for a wide community of people. Thus, the greater the love you give, the greater the mental wellbeing, whether spiritual or not. This suggests that mental wellbeing is profoundly dependent on the love you feel for others, and that the primary mental health benefits of spirituality may lie in developing greater love for others rather than faith or other factors.

"Mental wellbeing is profoundly dependent on the love you feel for others, and the primary mental health benefits of spirituality may lie in developing greater love for others."

Active practice of religion is associated with increased spiritualty and love

It is of course possible that those who feel more love for others are more likely to express spiritual connection rather than spirituality driving love for others. However, we show that the active practice of religion is also associated with increased spirituality and love for a wider community of people. This suggests that both spirituality and love for others can be cultivated through active religious practice. Conversely those without active religious practice or spirituality are still able to find their way to a greater community love, although with far less likelihood.

Countries with the lowest mental wellbeing have lower levels of active religious practice

Altogether the data suggests that active religious practice is a relatively reliable path to developing love for a wider community of people, and thereby better mental wellbeing. It is perhaps not surprising then, that the countries with the lowest mental wellbeing, such as the United Kingdom and Germany, have among the lowest active religious practice at 15% to 12% respectively. Conversely, in Latin American and Sub-Saharan African countries, which have much better wellbeing, active religious practice generally ranges from 60%-90%.

Active religious practice does not guarantee spirituality or feelings of love and care for others

However, it is important to point out that neither spirituality nor greater love and care for others are guaranteed outcomes of active religious practice. This may have much to do with the manner and focus of religious practice, surrounding cultural factors, and other life circumstances and life experience. It will be of considerable interest to understand what factors of active religious practice contribute to developing love and care for a wider community of people and how this understanding can help drive a better culture of wellbeing.

Methodology

The Global Mind Project

The Global Mind Project acquires data from adults age 18+ from the literate Internet-enabled world through a comprehensive online self-report assessment called the MHQ17,18. Participants are recruited through advertising on Facebook and Google by separately targeting populations in each age-gender group and geography across 65+ countries in 14 languages across a broad range of interest criteria. Individuals take the MHQ for the purpose of obtaining their mental wellbeing scores along with a detailed report offering self-help guidance.

Presently, 1000-2,000 people complete the assessment each day and are added to a dynamic database. In addition to the scored questions on mental feeling and function, respondents answer various demographic, lifestyle, and life experience questions.

The Global Mind Project is a public interest project that has ethics approval from the Health Media Lab Institutional Review Board (HML IRB), an independent IRB that provides assurance for the protection of human subjects in international social and behavioral research (OHRP Institutional Review Board #00001211, Federal Wide Assurance #00001102, IORG #0000850).

The Global Mind Project database is freely available to researchers in nonprofit and government organizations for non-commercial purpose. Access can be requested here.

The MHQ

The MHQ is a unique comprehensive assessment of mental wellbeing comprised of 47 elements of mental feeling and function including both positive assets, as well as problems that span the symptoms of ten major disorders17,18.

Within the MHQ, respondents rate each of these 47 items using a 9-point life impact scale reflecting the impact on one's ability to function. For items on a spectrum from positive to negative (spectrum items such as self-image) 1 on the 9-point scale refers to Is a real challenge and impacts my ability to function, 9 refers to It is a real asset to my life and my performance and 5 refers to Sometimes I wish it was better, but it's ok. For items with varying degrees of problem severity (problem items such as suicidal thoughts): the 1 rating on the 9-point scale refers to Never causes me any problems, the 9 rating refers to Has a constant and severe impact on my ability to function, and the 5 rating refers to Sometimes causes me difficulties or distress but I can manage. Respondents rate these elements based on their current perception of themselves.

The MHQ score is an aggregate score of mental wellbeing calculated from these 47 elements, and positions individuals on the spectrum from Distressed to Thriving, spanning a possible range of scores from −100 to +200. Negative scores indicate a mental wellbeing status that has significant negative impact on the ability to function (i.e. a status of distressed or struggling). It also provides sub-scores across 6 broad functional dimensions.

The MHQ is freely available online, is anonymous, and takes ~15 minutes to complete.

Data used in this report

Data used in this report included all responses obtained by the Global Mind Project between January 2023 and February 2024 (see associated tables for N values by age, gender and country) after the application of certain exclusion criteria described below. This resulted in a sample size of 239,692.

Data fields used in this report included 1) ratings to all 47 mental health questions 2) computed dimension scores and aggregate MHQ score and 3) responses to the following questions on extent of feelings of love of others; feeling of connection to a higher power, religious identify and active practice of that religion:

Assess the extent of your feelings of love (a desire for wellbeing) of others:

9-point scale where:

1 = I don’t love anyone

5 = I feel love towards very close family and friends

9 = I feel love towards a wide circle of people in my community

For the purpose of this analysis we divided the scale into three groups where 1-3 is labeled ‘No love, 4-6 is labeled ‘Family’ and 7-9 is labeled ‘Community’.

How do you describe your sense or feeling of connection to a higher power or the divine?

9-point scale where:

1 = None because there is no such thing

5 = Maybe I have one but I’m not sure

9 = It’s a strong and constant guiding force

For the purpose of this analysis, we divided this scale into three groups where a selection of 7-9 was defined as ‘Spiritual’, 1-3 as ‘Atheist’ and 4-6 as ‘Agnostic’.

Do you identify yourself with a particular religion?

- No I don't Identify with any religion

- Christianity - Protestant

- Christianity - Catholic

- Christianity - Orthodox

- Judaism

- Islam

- Hinduism • Buddhism

- Sikhism

- Other

Do you actively practice your religion? For example, attend services, practice rituals or prayers, read scriptures

- Yes

- No

Data Exclusion Criteria

Respondents who stated that they did not find the MHQ easy to understand were excluded. This exclusion criterion was applied by removing respondents who answered No to the final question in the MHQ which asks them “Did you find this assessment easy to understand?”. Also excluded were those assessments completed in under 7 minutes (the minimum time needed to read and respond to the MHQ), and those where response ratings had a standard deviation of less than 0.2, indicating that the same rating value was selected across all 47 rating items.

Data analysis and statistics

Average MHQ scores, average dimensional scores, and average ratings for each of the 47 problems and mental functions assessed were computed for all respondents altogether and for each age-gender group separately and overall averages were constructed as weighted averages of age-gender prevalence. These mean values as well as standard deviations, N values and P-values for all comparisons are shown in the associated data tables. The associated data tables include data from individual countries. Only countries which have >1000 responses are included in the table (51 countries)

References

1. Crocker, J., Canevello, A. & Brown, A. A. Social Motivation: Costs and Benefits of Selfishness and Otherishness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 68, 299–325 (2017).

2. Sprecher, S. & Fehr, B. Compassionate love for close others and humanity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 22, 629–651 (2005).

3. Gallup. The Mental Health & Spirituality Study. https://www.faithandmedia.com/research/gallup (2023).

4. Ngamaba, K. H. & Soni, D. Are Happiness and Life Satisfaction Different Across Religious Groups? Exploring Determinants of Happiness and Life Satisfaction. J Relig Health 57, 2118–2139 (2018).

5. Rosmarin, D. H., Pargament, K. I. & Koenig, H. G. Spirituality and mental health: challenges and opportunities. The Lancet Psychiatry 8, 92–93 (2021).

6. Lucchetti, G., Koenig, H. G. & Lucchetti, A. L. G. Spirituality, religiousness, and mental health: A review of the current scientific evidence. World J Clin Cases 9, 7620–7631 (2021).

7. Koenig, H. G. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 278730 (2012).

8. Koenig, H. G., Al-Zaben, F. & VanderWeele, T. J. Religion and psychiatry: recent developments in research. BJPsych Advances 26, 262–272 (2020).

9. Rim, J. I. et al. Current Understanding of Religion, Spirituality, and Their Neurobiological Correlates. Harv Rev Psychiatry 27, 303–316 (2019).

10. Rosmarin, D. H. et al. The neuroscience of spirituality, religion, and mental health: A systematic review and synthesis. Journal of Psychiatric Research 156, 100–113 (2022).

11. Pew Research Foundation. In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace. https://www.pewresearch.org/ religion/2019/10/17/in-u-s-decline-of-christianity-continues-at-rapid-pace/ (2019).

12. Gallup. Belief in Five Spiritual Entities Edges Down to New Lows. https://news.gallup.com/poll/508886/belief-five spiritual-entities-edges-down-new-lows.aspx (2023).

13. Pew Research Foundation. Why Muslims are the world’s fastest-growing religious group. https://www.pewresearch. org/short-reads/2017/04/06/why-muslims-are-the-worlds-fastest-growing-religious-group/ (2017).

14. Pew Research Foundation. The world’s most committed Christians live in Africa, Latin America – and the U.S. https:// www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/08/22/the-worlds-most-committed-christians-live-in-africa-latin-america-and the-u-s/ (2018).

15. Twenge, J. M. The Evidence for Generation Me and Against Generation We. Emerging Adulthood 1, 11–16 (2013).

16. Santos, H. C., Varnum, M. & Grossmann, I. Global Increases in Individualism. Psychological Science 28, (2017).

17. Newson, J. J. & Thiagarajan, T. C. Assessment of Population Well-Being With the Mental Health Quotient (MHQ): Development and Usability Study. JMIR Ment Health 7, e17935 (2020).

18. Newson, J. J., Pastukh, V. & Thiagarajan, T. C. Assessment of Population Well-being With the Mental Health Quotient: Validation Study. JMIR Ment Health 9, e34105 (2022).